The Aaron Douglas Cycle

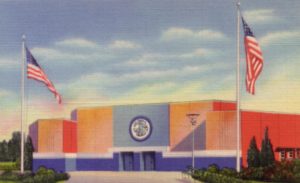

Raising awareness of the Aaron Douglas Legacy, the Hall of Negro Life, and Fair Park in Dallas, Texas.

Hi Everyone! I hope that you’re staying safe and productive during this time of social distancing.

Most of you know that I am an artist from AshStudios.Org. The Office of Arts and Culture has allowed me to do a “residency” to raise awareness of the work of Aaron Douglas – who in 1936 was an important part of the now destroyed Hall of Negro Life, which was a Pavilion built for the Centennial Texas State Fair in 1936.

African American Artist Aaron Douglas was from Kansas, moved to New York City and was a leader in the Harlem Renaissance, and was commissioned to paint murals for the Hall of Negro Life in Texas. His works were destroyed, against the wishes of the Texas black community, in 1937.

Only two panels of the four murals survived – one in the DeYoung Museum in San Francisco, and the other at the Corcoran Museum in Washington, D.C.

I was lucky enough to find out about his work through a visit to the Smithsonian Museum in D.C. in 2008.

As an artist that grew up in Dallas, I was shocked that a black historical art figure had created work for the North Texas community, and then further horrified that the powers-that-be in 1937 destroyed evidence of his legacy, while continuing to raise and maintain Confederate monuments.

This residency begins to change the injustice of that act, and, as a form of cultural reparations, highlight the Aaron Douglas Legacy, the Hall of Negro Life, and Fair Park.

Why is Aaron Douglas such an important artist to us? Aaron Douglas was generations ahead of his time in American Art. Douglas’s visions and working methods in visual art rivaled the developments in Modern Art that were happening in Paris and Berlin aka Picasso, Paul Klee, Kandinsky, Delaunay, etc.

“Unfortunately the Texas Centennial Commission chose to demolish the Hall of Negro Life in the spring of 1937 after futile attempts by the African American committee to keep it intact had failed. Along with the demolition, two of the four mural panels by Douglas were lost or destroyed. Fortunately Alonzo Aden had written a guide for the Dallas exposition titled “Educational Tour through the Hall of Negro Life” that was available to viewers and was reprinted in Southern Workman 65, no. 11 (1936): pp. 331-32.

Oil on canvas,

Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco

Corcoran Gallery, Washington, D.C.

Douglas’ series for Fair Park was comprised of four panels but what is presently known as Into Bondage (above), part of the Corcoran Gallery of Art’s permanent collection in Washington, D.C., and Aspiration, among the collections at the DeYoung Museum in San Francisco, are the only two extant panels. The first mural (now lost or destroyed) was devoted to the life of Estevanico (Little Stephen), a Moroccan slave who accompanied the Spanish explorer, Andrés Dorantes de Carranza, first to Florida and subsequently to Texas; Estevanico is acknowledged as the first black person to live in Texas. The second mural was known as the “Negro’s Gift to America” and featured, according to Aden who was quoted by Jesse O. Thomas, “ ‘agricultural workers on the left and the industrialists on the right’ ” bringing their gifts to “Labor.” All of the oil on canvas paintings related the advancement from slavery to becoming productive citizens in modern twentieth century cities such as Dallas.”

Quoted from :